The first-line pharmacological treatment, and only medications approved by the FDA, to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder are serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SRIs. These medications often only provide limited symptom relief, and usually take six to ten weeks to have a meaningful impact. SRIs also typically produce a wide range of unpredictable side effects for the user. In some cases, supplementing SRIs with antipsychotics can increase the effectiveness for a small percentage of patients, but this risks burdensome side effects even further. The need for alternative pharmacological options for treating OCD warrants research into new medications.

OCD and Ketamine

While the pathogenesis of OCD is not fully understood, it is known to be related to abnormalities in glutamatergic function — the function of the glutamate neurotransmitter within the brain. Irregular glutamate production and presence of glutamatergic compounds are strongly related to OCD symptoms and behaviors. The similarities between the pathogenesis of OCD and the mechanism of action of ketamine have led to research into its ability to lessen OCD symptoms.

Ketamine is an NMDA-glutamate receptor antagonist, meaning its main mechanism of action is in glutamate regulation. This, in addition to its reduction of brain inflammation, is thought to contribute to ketamine’s impact on depression symptoms. Additionally, previous studies have shown that ketamine has a significant impact on both treated and untreated individuals with OCD.

In 2013, Rodriguez et al. conducted a randomized crossover trial to further investigate ketamine’s effects on obsessive-compulsive disorder. The randomized, controlled, double-blind, crossover study included 15 medication-free adults with OCD. All individuals also experienced near-constant obsessions to improve the ability of attributing symptomatic change to the study drug. The crossover method allowed each participant to serve as their own control, allowing for a smaller sample size and reduced variability.

Methods and Measurements

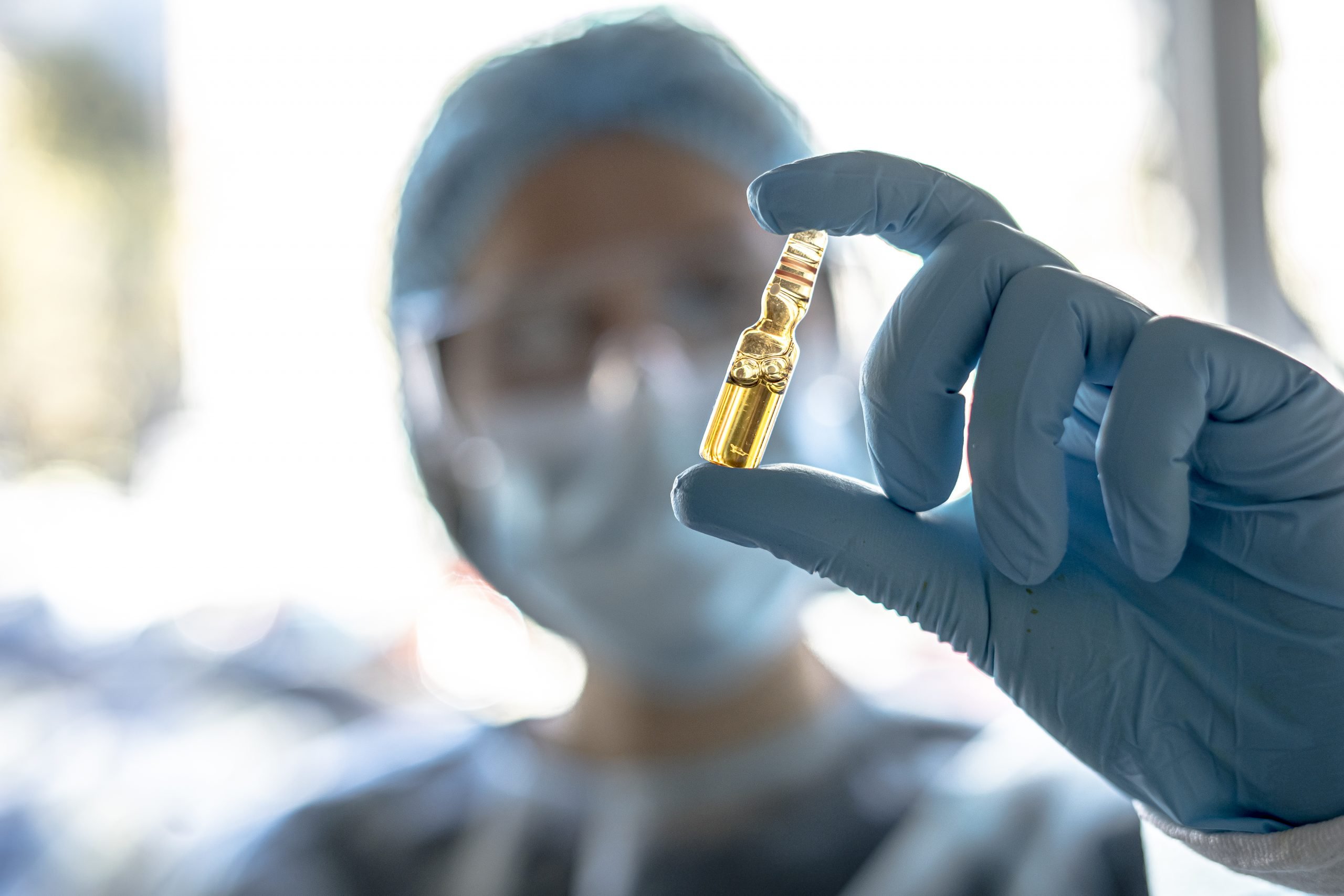

All participants received two intravenous infusions over 40 minutes each. One infusion contained ketamine at a dosage of 0.5mg/kg, and one contained saline. Infusions were administered 1 week apart and the order of infusions was randomized.

Patients self-rated severity of obsessions with the OCD-VAS scale in order to measure rapid changes in obsessions during and after infusions. Only obsessions were measured during this time because compulsions were constrained as patients were connected to stationary monitoring equipment. Additionally, an independent evaluator assessed patients at baseline and one week after each infusion using the Y-BOCS.

A variety of assessments were also used to measure side effects and tolerability of treatment. To evaluate severity of depression, the HDRS-17 was used at baseline, 1 day post-infusion, and 3 days post-infusion. The degree of dissociation (CADSS), manic symptoms (YMRS), and psychotic symptoms (BPRS) were assessed by a study psychiatrist at various times throughout the study, and possible side effects were evaluated.

Results

Altogether, 8 patients were assigned to receive the ketamine infusion first and saline infusion second (arm A), and 7 patients were assigned to the opposite order (arm B). Patients in arm A on average did not return to baseline OCD-VAS scores before receiving the saline infusion, indicating a significant carryover effect. There was also a significant carryover effect observed in Y-BOCS scores. The mean baseline score for both assessments was significantly lower at the saline second infusion compared to all other three infusions (ketamine first, saline first, and ketamine second).

Only first-phase data was examined in additional analyses to measure the effectiveness of ketamine independent from carryover effects. OCD-VAS scores differed significantly at mid-infusion, 230 minutes post-infusion, and 7 days post-infusion between ketamine-first and saline-first groups. Additionally, 50% of ketamine-first patients met criteria for meaningful treatment response as assessed by Y-BOCS scores (≥35% decrease), compared to 0% of saline-first patients.

Individuals who received ketamine first and ketamine second showed no significant differences in OCD-VAS score reduction. At 7 days after infusion, one of seven met the criteria for meaningful treatment response (≥35% decrease in Y-BOCS score).

Reported side effects were consistent with prior studies that use sub-anesthetic doses of intravenous ketamine. Symptoms of dissociation, positive psychotic symptoms, and conceptual disorganization were most often reported mid-infusion, which all resolved by the 110 minute post-infusion mark. As for physical side effects, the most commonly reported symptoms included dizziness (n=3), headache (n=2), nausea (n=2), vomiting (n=1). All physical side effects were also resolved by the 110 minute post-infusion mark. No side effects were reported in the week post-ketamine infusion.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that participants showed rapid and significant reduction in obsessions immediately following ketamine infusion, and reductions persisted until beyond the 1-week post-infusion mark. Additionally, half of the ketamine-first patients experienced a significant reduction in compulsions one week post-infusion. The carryover effects suggest that ketamine’s impact on OCD symptoms last longer than previously reported.

This demonstrates that even without the presence of an SSRI, a drug that affects glutamate neurotransmission can reduce OCD symptoms significantly. These results are consistent with the glutamatergic hypothesis of OCD and align with prior research on ketamine’s effects on OCD symptoms.

Further research into understanding ketamine’s mechanism of action and repetition of the trial with a greater sample size are needed. This study supports the growing body of evidence that ketamine is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for individuals with OCD, and a promising alternative to SSRI medications.